You may have seen our new “Rivers of Reading” activity, which launched yesterday. The Rivers of Reading methodology (Cliff Hodges, 2010) facilitates children to think about their reading journey to date holistically, around critical incidents. In my research funded by the UK Literacy Association published this week (Little, 2021), I explore Rivers of Reading with multilingual children, and highlight why, although the activity is fantastic for *all* children, it is particularly for children who read in more than one language.

Why “Rivers”? The metaphor drawn from nature works particularly well because our reading experiences, like rivers, are unique, constantly evolving, and cumulative. It shows children that, just like rivers that pick up additional water sources along the way, so everything we read adds to our own development. The metaphor makes no judgment regarding reading materials, it simply asks pupils to identify what certain parts of reading material have contributed the the overall picture – the “river”.

Appleyard (1990) charted the development of “becoming a reader” as follows:

- The Reader as Player (the early years) – understanding the concept of stories, engaging with a fantasy world, exploring how the fantasy world relates to reality, using this to safely explore alternate realities.

- The Reader as Hero/Heroine: Identifying with characters, using reading as a way to escape or access a different world

- The Reader as Thinker: During adolescent years, choosing literature that questions the status quo and is critical/rebellious of surroundings

- The Reader as Interpreter: Systematic reading to explore a topic, often as part of formal learning

- The Pragmatic Reader: Appleyard states that, once all these avenues have opened up to the reader, we happily use and adopt the various roles to match our mood and our lifestyle, swapping as necessary and preferred.

I have to admit that I don’t necessarily agree with everything Appleyard states (for example, he writes that the “Reader as Hero/Heroine” seeks to escape to a less complex world, whereas I believe that there are plenty of very successful books for young children that are incredibly complex).

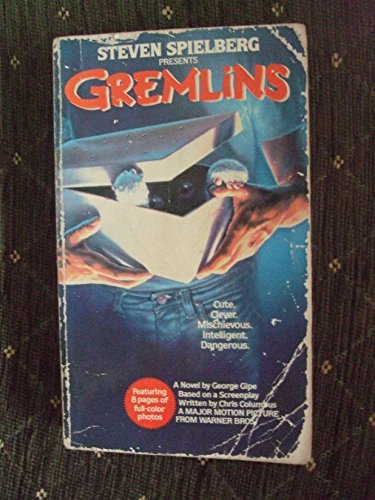

Nevertheless, when multilingual children read across their various languages, they often develop asynchronously, and issues can arise when intellectual development and literacy development get “out of synch”, and they cannot access books they need or want. When we look at children’s Rivers of Reading (especially multilingual children, and/or children whose literacy levels are developing asynchronously), we often find books that speak of specific successes or frustrations, and books which are included because they represent a “first” – I have a “first” myself, in my River of Reading, a dog-eared second-hand copy of Gremlins, picked up in a second-hand Oxfam shop in Falmouth on a school exchange when I was 14 years old, for 25p.

It is the first book I managed to read cover to cover in English. It is not my favourite book, and it’s certainly not high literature. In fact, I picked it up because I kind of knew the plot (although I hadn’t seen the film), so it was lower-risk. I picked it up with the sole intention of reading a book in English, and I succeeded, which was an incredibly powerful feeling. I suppose I would also add Lord of the Rings, which I picked up in the same bookshop, tried to read after my success with Gremlins, and failed miserably… Giving children the opportunity to reflect on what books (and other reading resources) they consider “important”, rather than “favourites” opens up conversations and can help children to view their reading experiences overall more positively.

When children construct their River of Reading, it is important that they have help, to make them think about their earliest reading experiences – the “source” of their reading journey. Grown-ups can help with that, to identify favourite books from early childhood. In many families, conversations about the River of Reading open up conversations about reading in general, as well as about biliteracy development, giving children the opportunity to share frustrations and success stories. It also helps immensely to make home reading (in any language) more visible in school contexts, for children to identify and express preferences, and, typically, leads to children being surprised at the amount of reading they have done, so that even children who might typically state that they are “not a reader” can have a feeling of success and affirmation.

The activity takes a while to complete, so it is perfect to set up now, for a big “reveal” around World Book Day, or to set up at World Book Day, for a big reveal for the International Day of Multilingualism on 27th March. We would love to see your children’s Rivers of Reading!

References:

Appleyard, J. A. (1990) Becoming a Reader: The Experience of Fiction from Childhood to Adulthood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cliff Hodges, G. (2010). Rivers of Reading: Using critical incident collages to learn about adolescent readers and their readership. English in Education, 44(3), 181-200. DOI: 10.1111/j.1754-8845.2010.01072.x

Little, S. (2021): Rivers of multilingual reading: exploring biliteracy

experiences among 8-13-year old heritage language readers. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, DOI: 10.1080/01434632.2021.1882472